This article is an archival reproduction of an article originally written by Iqbal Masud and published in the Indian Panorama Catalogue of 1986. Some of the images have been taken from the original article.

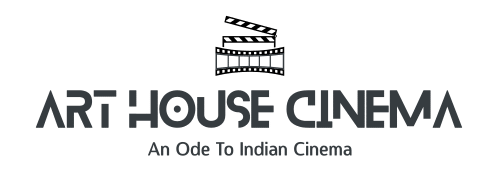

Someone once compared Smita Patil to Anna Karina, the iconic figure of the French New Wave of the sixties. I remember being slightly annoyed when I read this. Why turn someone so essentially ‘Indian’ into an imitation icon? But when I sat down to write this tribute (a painful task for me) I recalled a tribute to Anna which perfectly fits Smita… “how intense an impression a girl can make if she knows how to be filmed if she divines how the camera exploits her, and yet still consents to it without mannerism, irritation, or prudishness.”

Benegal, her discoverer, was right when he singled out ‘presence’ as Smita’s first notable quality. Those who missed her early TV appearance missed something. I saw her on the box long before she became a star. Her mere presence became a pleasure. I remember one program where she sat slightly outside the discussion circle, intervening rarely. One couldn’t concentrate on the discussion. Smita’s shimmering quality of radiance enveloped the small screen. It was when you met Smita that you realized that the screen image was less powerful than the real-life one. Her eyes, her gaze had a special quality – it looked at you, sized you up, troubled you, occasionally looked beyond as if searching for some unattainable object. It was this intriguing somewhat ‘lost’ quality of her look that Benegal marvelously captured in Nishant and Kondura and Rabindra Dharmraj in Chakra. The “presence” of Smita is unmatched in the history of Indian cinema.

Smita Patil, Manthan (1976)

To that presence was allied an enormous vitality. It was much more than effervescence, or ebullience (and this is where she went beyond Anna). It was vitality compounded of sensuality, earthiness and a certain rock-like (this may sound odd but I cannot find a better expression) integrity. What gave a special edge to this vitality was a kind of vulnerability, even fragility with went with it. Smita displayed a flash of all this in Manthan.

‘Smouldering’ was the word most often used to describe this quality. It did not do justice to Smita. In Manthan Smita showed the sexual need and withering contempt for its lily-livered rejection. Bhumika showed avidity for life, bitter marital struggle, the traps that await the bright and hungry-for-experience women. There were some ups and downs in the film, but the mixture of aestheticism and a tigerish sense of freedom was unforgettably rendered by Smita. A director very different to Benegal, Ketan Mehta, used Smita’s brand of vitality in a very different way in Bhavni Bhavai. Here psychological individuation was not attempted. There was an orgiastic revolt, an abandoned carousal. Smita sparkled here in a kind of gypsy-impish-elfin-mocking, impulsive note.

In the week at Nantes (France) I spent with Smita, Girish Karnad, and Adoor Gopalakrishnan, a few years ago (we had gone there as members of a film delegation), I experienced both the vitality and sprightliness. If I struggled with a suitcase hurrying to the train in the freezing December air, Smita would seize it and march off. Being with her was great fun but also a rollercoaster ride. She was no hypocrite. If she was bored with you, she was bored with you. But if you said something that held her, she would become alive.

Mirch Masala (1987)

I remember one particular incident. The Indian delegation were guests of honour at the Nantes mayoral function. As we marched up to the hall, Girish, Adoor, and Smita decided that I should introduce them. Then, to their horror, they noticed I wore no tie. “You are all climbing up, so you have to dress up. I am retiring this year, so I gladly dress down,” I said. Just before she entered the glittering hall, Smita turned to me and said, “You know you are slightly mad. So am I.”

And that brings me to Smita’s third quality. E.M. Foster said: “An artist needs to be an outsider.” Smita was a genuine outsider, not a stage one. When she tried stagey ‘outsider’ roles, as in Haadsa or Arth, she failed. But her slightly off-center attitude for life, her non-conformism, her bluntness, her inner fire ran like an enriching stream beneath all her performances. She has been called insecure, even neurotic. But all this was the very sine qua non of her screen persona. Take her roles in Umbartha or Bazaar. An apparently straight role in Umbartha rose to great heights in the few minutes she confronted the one-man commission with intensity and honesty. Even in an uneven film like Bazaar she brought off that unforgettably tragic scene where mothers press their daughters on her to be married off. The acme of the outside Smita was of course Tarang – willing dupe of the enemy class, yet their final betrayer. I have ambivalent feelings about her foray into ‘mainstream’ cinema. There were a few modestly good efforts: Bazaar, Amrit, Bheegi Palken were among them. But these remained few. I had strong disagreements with Smita on this point on the few occasions we met. She tries roles of harrowing poverty, of ‘heroic’ stern women. No go. She came from the grey world of middle-class complexity and she played best on home ground. I think she was a congenital outsider, desperately trying to become an insider in the formula-ridden mainstream cinema.

So how does one sum up Smita’s achievement? At the risk of being misunderstood, let me say that she remained an actress in search of a director. An actress of her quality, with her concealed passion, despair, and love of life deserved a Bergman, a Bunuel, or a Renoir. But at least young Sandeep Ray got a superlative performance out of her in his TV episode Abhinetri.

If her work is viewed in totality and if the history of our cinema were to be written at this moment, I shall rank her with Nargis and Nutan at the top. A few months ago she sent me a scribbled note, hauling me over the coals for my ‘personal’ criticism, praising one of my short stories. Then she added in a typical P.S. “People say I am undiplomatic. I shall become diplomatic when I grow old. And that’s a long way off.”

Today the memory of that note is both lovely and tragic.

– Iqbal Masud

(Courtesy: Express Weekend)

About The Author

Iqbal Masud (born as F.C. Jilani in 1920) was a noted film critic and columnist known for his flair for writing insightful film reviews. He authored books like Dream Merchants, Politicians & Partition, and featured regularly in newspapers like the Indian Express. He passed away in 1999 in Mumbai.

This article was first published as a tribute to Smita Patil by the author after her death in 1986.